My Life with the Battle Poet.

It was the summer of 1977 that I first ran into Malcolm at a dance in our home town. I remember the place: the glorious modernist Riverside ballroom, part of the New Brighton baths complex that was later destroyed in a storm. Inside, thugs and students eyed up the local talent. I was there with my mates; a motley crew of druggies, lefties and punks. You could have cut the atmosphere with a knife – that’s why everyone was armed.

Suddenly, a gasp went up, the crowd parted and a big, burly bully burst in. Six foot seven in his leper-skin levi’s, a youth stood aloft, bursting to shout.

His bold entrance sent ripples of gossip around the room.

”Who is that?”, I enquired, urgently.

”It’s Malcolm Bennett”, they went.

‘’He’s a poet!’’. ‘’He’s a Nazi!’’. ‘’He’s bent!’’.

Knives, pints and slags were fingered, nervously.

”Hmm,” I thought through gritted teeth. ”He looks interesting and yellow.” But, before we could chat, a fight broke out and sirens cleared the dance floor. Later, I discovered he lived next door but one to me in Egremont, a feral squat that lapped the shores of the Mersey. I’d see him gangling up the road to the shop, his Glen Campbell fringe and polyester cardigan flapping gloomily in the smog. He was grumpy and serious and committed to his poetry. I once painted ”Happy Birthday” on my naked girlfriend and sent her round to cheer him up. He slammed the door in her face. He thought I was a frivolous party animal with no commitment to my art. I thought he was an old fart, stuck in his gloomy books instead of girls. However – he introduced me to Camus, Celine and Jack London.

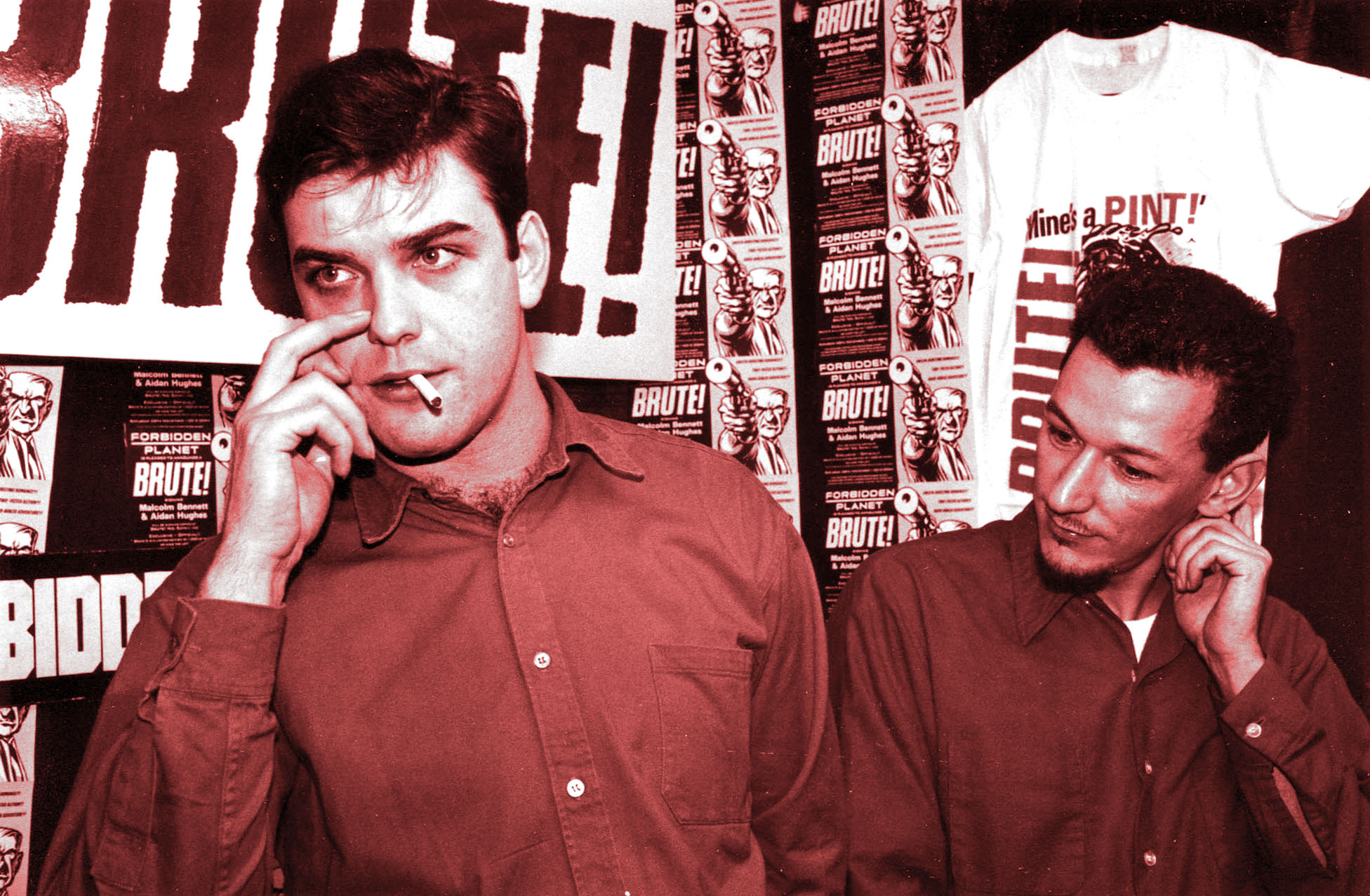

I read his poetry and was impressed. I suggested Malcolm should read it over an improvised sound-scape. We practiced, stuck up posters and played at Eric’s club. To earn money, we dressed up as terrorists and stormed local pubs, threatening the regulars with fake guns to the amusement of practically everyone. We commandeered a school bus dressed as revolutionaries. We hired burly psychiatric nurses to beat up our bass player on stage. So many stories….

While Mal was in prison for an altercation with the police, I moved to Bristol to start a new operation whilst obtaining a better standard of benefits. When he eventually emerged from Walton nick, he joined me there and we began to start performing and publishing.

I’d been in town a while and met a new circle of people but Malcolm took over as soon as he arrived in the city. He became legendary for striding into St. Paul’s notorious Black and White club to complain about the standard of their weed and getting away with it. We spent the winter months writing and freezing in The Unit and the summers performing and selling books on the street, at festivals and at protest marches in the UK and Europe. Despite the unemployment and black mood that had settled over the country, Malcolm and I were inspired: the Thatcher government, the Miner’s Strike, the Falklands War and the Anti-Nazi League protests fueled our creative fury.

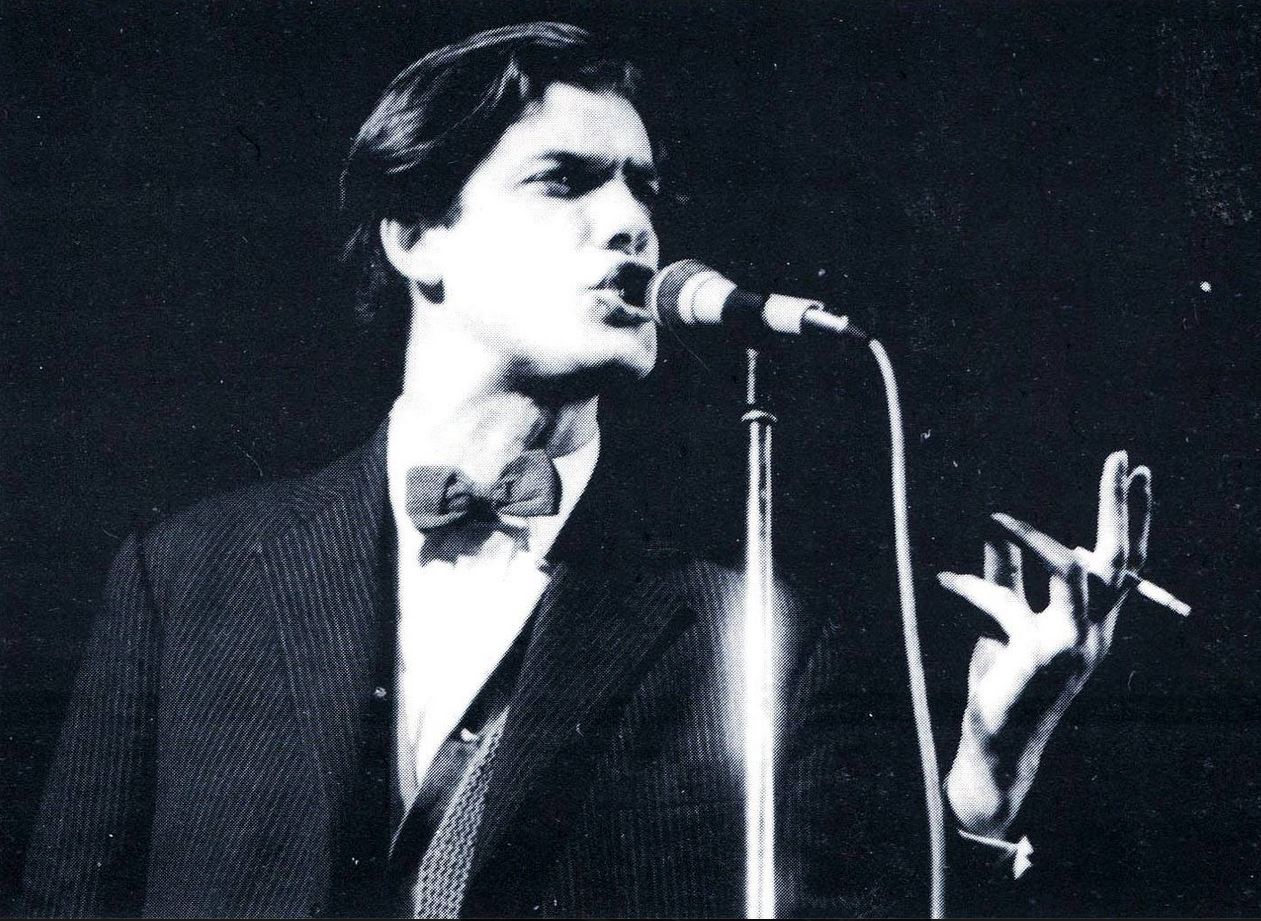

Amsterdam in the early 80s offered us new opportunities and Malcolm gave his most electric performances in the city, appearing at the One World Poetry festival two years in a row.

We decided to gatecrash the event (which featured, along with William Burroughs, Russia’s greatest living poet, Yevgeny Yevteshenko and the UK’s Gregory Corso. We had a lot of support in the city so it didn’t take much blagging before we got the nod from the organiser that we could go on before one of the night’s headliners. Unpacking our Roland 606 and 808 on stage, we surveyed the room, packed to the rafters with poets, punks and fans eager to see the legendary Burroughs in action. After performances from Corso and others, we shot onstage and, for 30 minutes, regaled the audience with our brand of high-octane electro demagoguery. Filled out with our supporters, the audience went mental, clapping wildly and urging us into several encores until, spent of energy and other material, we triumphantly legged it off stage and into the VIP bar which overlooked the main hall. Meanwhile, Old Bill took to the stage and proceeded to croak his way through a medley of his ancient hits, pausing briefly to survey the hall which was half-empty after our storming finale. So, we were into our fifth pint before Bill, along with his entourage, approached us at the bar and proceeded to accuse us of stealing his notes, drugs and wallet while his bony ass was on stage. His minder, while a strapping lad himself, noted Malcolm’s 6′ 6” fighting stance and baulked at Bill’s suggestion of a quick frisk to determine our innocence. ‘You’re off your head, mate,’ I laughed, ordering another round.

Malcolm, unfazed by Bill’s temper tantrum, suggested that the old timer check his own pockets before hurling unfounded accusations. The minder whispered in the elderly poet’s ear before Bill, his eyes glazing over, began to timidly search his pockets. Meanwhile a crowd, eager for some inter-poet rivalry, surged round us as Bill emptied his coat. There, in amongst the junkie flotsam, we could see the items he’d accused us of taking so his minder wisely took the opportunity to whisk him away.

Malcolm could not resist one parting shot. ‘You know, Bill,’ he yelled over the heads of the crowd, ‘You should stick to Guinness. It’s a lot better for your memory than heroin’.

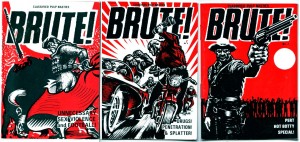

Also at this time, we began to write the initial stories that would become the first issue of BRUTE!

In the mid-80s, Malcolm moved to London and, after a period living in poverty, managed to get himself an internship at Blink Studios in Soho while touting BRUTE! around various ad agencies and TV production companies. It paid off. He gave me the call and I moved to London, immediately. We both lived on the notorious Rockingham estate in Elephant and Castle with dozens of other scousers fleeing the bleak unemployment of the north. They even called the estate, ”Little Wallasey” due to the amount of squatters who’d moved down south from the Wirral. Before long, we entered into a period of sustained creative work producing short films, pop videos and ad campaigns all based on the BRUTE! concept. Malcolm’s unbridled enthusiasm, wit and bravado secured us jobs and press coverage until his rising star was recognised by channel chiefs eager to unleash unconventional presenters onto the world via the new medium of youth TV. By the time we parted company in 1989, Malcolm was appearing on TV twice a week.

Except for an fruitless reunion in Bristol in the mid-90s, I wasn’t to see him again for 25 years. I moved with my family to the States and put the work I’d done with Malcolm behind me. It wasn’t until his son,Tom, urged us to start talking again a few years back that we began to heal the old wounds and started talking about working together again. When he visited me in Prague last year, he seemed his old vivacious self, brimming with ideas for the future and looking forward to seeing BRUTE! on the book stands once more.

Sadly, he never lived to see his final book published.

Malcolm Bennett performing extracts from his anti-Thatcher polemic, The Claim.